Unveiling Pennsylvania's 19th Century Vital Record Registrations

We are going back to 1800s and uncovering the vital record registrations, including birth registrations to marriage registrations to death registrations. We'll cover a history of vital record registrations, the types created, and where to find these records today.

There is no time more confusing for genealogy research in Pennsylvania then the 1800s.

In this article, we will take you back to that time period, uncovering the vital record registrations that were created by counties and cities. From birth registrations to marriage registrations to death registrations, these valuable documents provide a wealth of information for those seeking to trace their family roots.

We'll cover a history of vital record registrations in Pennsylvania, the types of vital records created, and where to find these records today.

History of Vital Record Registrations

Prior to Pennsylvania issuing birth and death certificates through the Department of Health, counties and large cities conducted registration of births, marriages, and deaths. These vital record registrations used a variety of forms and were implemented in different ways over the nineteenth century. It is confusing and contradictory time period, and this article will lay out the various registration attempts by both time period and locations.

The first vital record registrations began as soon as William Penn arrived in the state in 1682. For details on those records during the colonial period of Pennsylvania, 1682–1789, see The Rare Colonial Period Vital Records of Pennsylvania.

The main difference between registrations of births, marriages, and deaths and the later certificates is the look of the record itself. While certificates detailed in Chapters 3 and 4 were completed on individual forms with many people providing information, registrations were completed in ledger books by a single courthouse clerk. Doctors, midwives, funeral home directors, parents, and local registrars, all could be signing and providing information on certificates. On county registrations, it is often not known who provided the information to the clerk, and it could be recorded weeks to months after the event occurred.

Implementation of registrations by counties and cities in Pennsylvania was directed by state law, which specifically defines what is to be collected, when, and by whom. Later, when the Department of Health was formed, many of the rules around birth certificates and death certificates were dictated by policy boards and not widely published.

Most of the counties followed similar vital record registration processes. The one exception is the City of Philadelphia. In 1854, Philadelphia County consolidated the townships and boroughs within its border and became the City of Philadelphia. After 1854, there was no longer a Philadelphia County. Yet today people will sometimes refer to Philadelphia as a county.

County Registrations, 1852–1854

In the mid-19th century, Pennsylvania made its first attempt at county-based vital record registrations. Between 1852 and 1854, 48 counties, including Philadelphia, initiated these registrations. However, compliance during this period was disappointingly low, and very few individuals registered their births, marriages, or deaths at the county courthouses. The reasons for this lack of participation remain unclear, but the state law requiring registrations was eventually repealed in 1855.

|

Adams |

Delaware |

Montgomery |

|

Allegheny |

Elk |

Montour |

|

Armstrong |

Franklin |

Northampton |

|

Beaver |

Greene |

Northumberland |

|

Bedford |

Huntingdon |

Perry |

|

Berks |

Indiana |

Schuylkill |

|

Bradford |

Juniata |

Somerset |

|

Bucks |

Lancaster |

Susquehanna |

|

Butler |

Lawrence |

Tioga |

|

Cambria |

Lehigh |

Union |

|

Carbon |

Luzerne |

Venango |

|

Centre |

Lycoming |

Warren |

|

Chester |

McKean |

Washington |

|

Columbia |

Mercer |

Wayne |

|

Cumberland |

Mifflin |

Westmoreland |

|

Dauphin |

Monroe |

York |

Revival of Vital Record Registrations: 1893-1905

A second attempt at vital record registration took place between June 6, 1893, and December 31, 1905. During this period, each county's Orphans Court maintained registers for both deaths and births. Although the level of compliance improved compared to the previous attempt, it still fell short of 100 percent. The completeness of these records varies across counties, and researchers should consult the Pennsylvania Bureau of Health for access to these registrations compiled and sent by the counties.

City Registrations: A Unique Perspective

Some of Pennsylvania’s largest cities had their own Departments of Health or Bureaus of Health, which were required under state law to set up their own birth and death registration systems. Researchers will find the forms and information collected for vital records varied from city to city. Individuals living in cities were registered within the city only, and not the county the city was situated in.

Vital record registrations by counties and cities was short-lived. On April 27, 1905, the Pennsylvania State Legislature created the Department of Health and replaced county and city registrations with a uniform state-wide certificate system.

Purpose of Vital Record Registrations

The purpose of death registrations was clearer than birth registrations.

A registration with the city’s Bureau of Health was necessary to obtain a burial permit for a local cemetery. Registration was also required to transport the deceased out of town for burial. In all areas, being put on the death register removed an individual from the tax rolls.

Researchers will find death registers in rural counties have batches of individual registrations entered around when county taxes were due in spring and fall. These registrations were for deaths that occurred weeks to months prior. Failure to pay county taxes meant fines and possible confiscation of property, so families made sure to register their deceased relatives.

Entering a death in the county or city registration book also met the requirements of Pennsylvania state law to settle estates. Legislation passed on May 15, 1874 stated that estate could not enter probate without affirmation of the date, time, and place of death of the deceased. In probate files prior to 1893, researchers will find small pieces of paper with this information, accompanied by the signature of a witness to verify the information. Death registers and later death certificates took over this verification of death to open up an estate.

Birth registrations did not have as much of a purpose as death registrations. Children did not need to be registered with the county to attend school or receive medical care or use the registration for any identification.

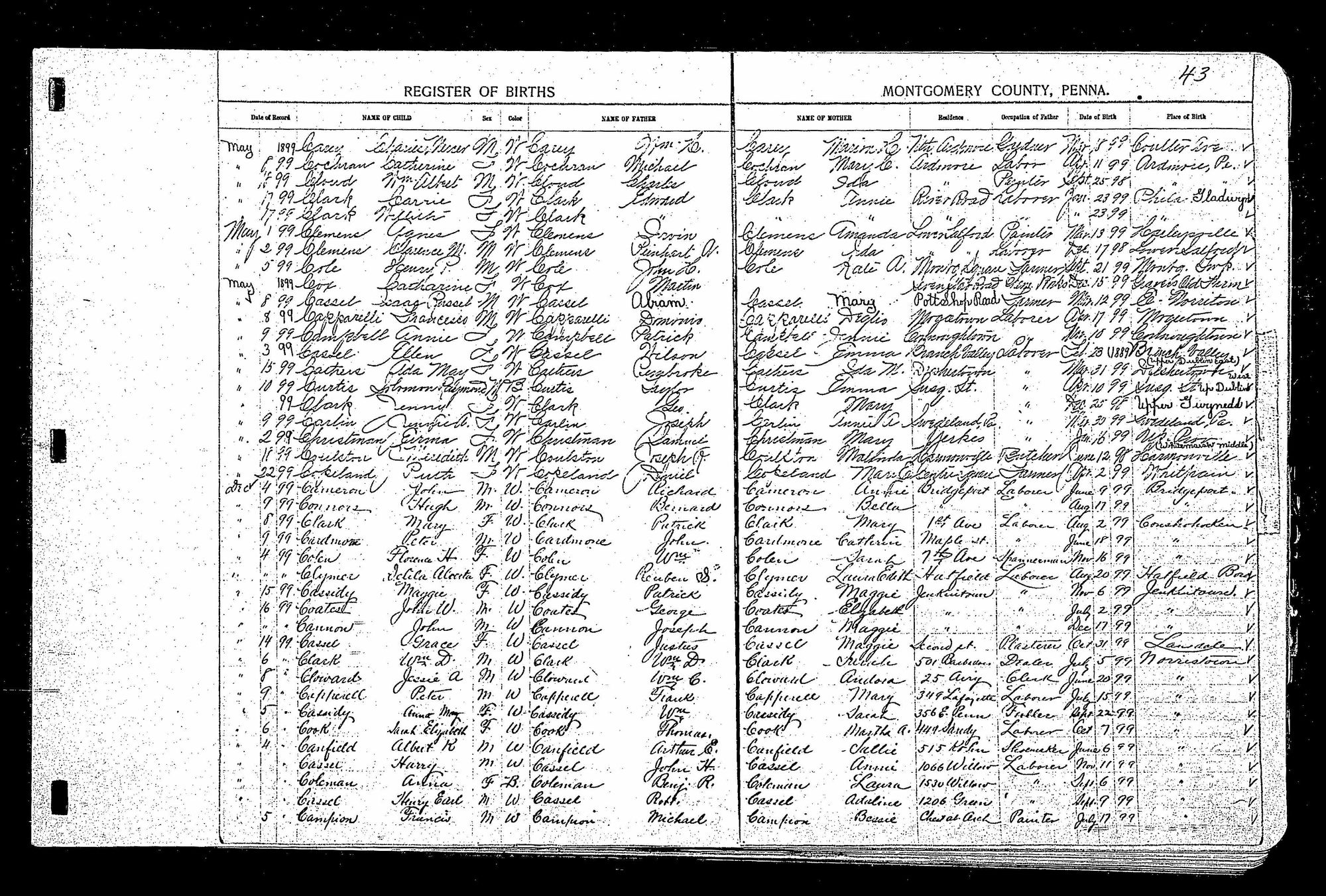

Information Collected on Local Registrations

In most counties, vital record registers are large 18-inch by 24-inch ledger books, weighing several pounds each. There are multiple entries per page, either in columns going across or blocks of four on a page. The state defined the information to be collected, not the exact form for collection. This means researchers will find variations from county to county, county to city, and city to city.

Death Registers

Generally, the following required information may be noted:

- Full Name of Deceased

- Color/Race

- Sex

- Date of Death

- Age at Death

- Married or Single

- Residence

- Length of Time at Residence

- Occupation

- Cause of Death

- Onset/Length (of illness)

- Parents’ Names if Minor

- Parents’ Birthplace

- Physician Name/Signature, Address and Date

- Undertaker Name, Address and Date

- Burial Place/Cemetery

- Date of Burial

- Registrar Name and Date

Marriage Registers

Generally, the following required information was noted:

- Full Names of Bride and Groom

- Color/Race

- Sex

- Age

- Previously Married?

- Residence

- Length of Time at Residence

- Occupation

- Parents’ Names if Minor

- Parents’ Birthplace

- Date of Marriage

- Registrar Name and Date

Birth Registers

Generally, the following required information may be noted:

- Full Name of Child

- Color/Race

- Sex

- Date of Birth

- Residence

- Parents’ Names

- Parents’ Birthplace

- Physician Name/Signature, Address and Date

- Registrar Name and Date

Process to Complete Local Registrations

The county and city registration process for deaths started with physicians. State law compelled physicians to report on the deaths of those in their care. In the nineteenth century, doctors made home visits for those at the end of life. Hospital use was uncommon in cities and non-existent in rural areas. For birth registrations, midwives in addition to doctors would submit information.

The registration was done in person at the county courthouse at the Register of Wills office. Researchers will notice in death registration records that physicians sometimes reported two or more deaths in one courthouse visit. The reported deaths could have occurred days or weeks apart. Timeliness was not required!

In the nineteenth century, heads of households and men over age eighteen paid taxes to the county. Tax collectors were assigned to each municipality – township, borough, or city – and would go door-to-door to collect what was due each spring and fall. If the tax collector came to a property and found that some of the taxable residents had died, he would report the death to the Register of Wills office and sometimes mark the resident as “deceased” in his tax roll.

Wives, single women over eighteen, and children did not pay county taxes and were not listed on local tax rolls. Because of this, when women and children died in the nineteenth century, their deaths were not always reported. The exception here, of course, was women who were heads of households and responsible for taxes, particularly in rural areas, where up to 20 percent of properties in a township could be headed by women. Those women would be on the tax rolls and when they died, they were likely on the death register.

Death registrations were typically kept in ledger books with multiple entries per page. In some places there are single line entries with columns going across a two-page spread. In other places there are two or four sections per page for each registration. Researchers must take care to obtain all the registration information.

How to Find Vital Record Registrations

The Register of Wills at the county courthouse typically kept birth, death, and marriage registrations. In some counties, the records will be found at the Orphans’ Court office.

Not every county kept early vital record registrations into the twentieth century. The few county records between 1852 and 1854 that survive are digitized on Ancestry. These registration books are large ledger books with multiple records per page.

Vital record registration records from 1893 to 1905 could be in ledger books or on single sheets of paper. Most of these have not been digitized and the relevant county needs to be contacted directly for access to the records.

In Philadelphia, birth and death registrations were filed on individual paper forms. The Philadelphia forms used also changed over time. They are stored today in boxes at the Philadelphia City Archive. These vital records have been microfilmed and digitized by FamilySearch.

Checklist for Searching

- First know the county the person died in. If unsure, look at the cemetery record and last census record for the county of residence.

- County genealogical societies often have indexes of the birth, marriage, and death registrations. These were completed before the internet and are often useful to find records. The index will let you know if there is a original record to search for.

- For city and county birth and death registrations, the primary online source is FamilySearch. FamilySearch microfilmed many courthouse records in the mid-to-late twentieth century. These microfilms are typically records from the beginning of the county to the early twentieth century. (Dates vary considerably by record type and by county.) All the FamilySearch microfilms have been digitized and are viewable online as images. Some images are indexed and computer searchable. Go to familysearch.org then go to the catalog and type in “Pennsylvania, [County Name]” (where County Name is the county you want) to search what county records they have.

- The 1852–1854 registrations are on Ancestry in these three databases:

“Pennsylvania, U.S., Births, 1852-1854”: ancestry.com/search/collections/2349/

“Pennsylvania, U.S., Deaths, 1852-1854”: ancestry.com/search/collections/2487/

“Pennsylvania, U.S., Marriages, 1852-1854”: ancestry.com/search/collections/2486/

- Ancestry does not yet have indexed birth and death registrations for other years and locations. The primary online source for these county and city records is FamilySearch.

- To assist in the search, be sure to use variations of the spelling of the first name and surname.

- Be sure to collect the registrations for all related family members of the deceased. Analyzing these will provide details to the lives of your primary research subject.

Genealogy research in Pennsylvania is challenging because of the variations in vital records in the 19th century. By unveiling the history of vital record registrations, we gain a deeper understanding of what records were created in different places and how to find them. Vital record registrations can be a challenge to locate, but they may have the answers you have been seeking for your family tree.

© 2019–2023 PA Ancestors L.L.C. and Denys Allen. All Rights Reserved.